Why Origin Stories?

Read their story. Grow the courage to write your own.

Welcome to Origin Stories, where I share the stories of ordinary people who achieved the extraordinary - finding a purpose and work they love.

This project is very personal to me. For a long time, growing up, I thought the way to choose a career was to pick the most financially rewarding and respectable work I was capable of doing, and then mold myself to its requirements so effectively that I could get to the top of my field.

It never occurred to me that I could pursue something I was curious about for the simple reason that I enjoyed doing it. It’s taken me 15 years to fully understand this and to take the plunge. The key thing that helped me along were people’s stories.

And that’s what I would like to share with you: the questions people faced, the decisions they made, how those worked out (or didn’t work out) and how they ultimately found their way. I hope that by reading their stories, you - like me - will grow the courage to write you own.

My Story

In high school, I was a good all-around student - math, sciences, languages, humanities, and art. It all came fairly easily to me. Well, all except music and team sports. But no one really expected me to be good at music and team sports. For my next step, I needed to pick among medicine, science or engineering, because I was smart and got good grades. I think even law would have been considered sketchy by my family, and business was definitely off-limits.

I loved art, especially sculpture. I had a facility with foreign languages and persuasive essay writing. I was obsessed with windsurfing. If you had asked me what I had wanted to be at 15, I would have said: CIA agent, sculptor, or professional windsurfer. It never occurred to me for a single second that any of those were open to me.

I read a book where the main character was an architect, and I think that’s what put architecture on the table. It was what we called a “rotten compromise”: architecture can be an engineering degree, which made it acceptable to my parents, and there was enough art in it to make it palatable to me. Despite growing up in Canada speaking English and French, I started my studies in 1990s Poland in Polish. I was completely unprepared for the rigour of the program I entered, and clawed my way up from barely passing my first year to the top 5% of my class at the end of my third.

While I conquered history of architecture, structural engineering and project management, my nemeses were design projects. I was pretty good at organizing a floor plan, but I had no opinion on how the building was supposed to look like in 3D. Wood or concrete? Steel or glass? I had no idea. I felt horrible shame when I stared at a blank page. I knew I ought to get good at this, since it was my chosen profession, and I felt like I was failing because I couldn’t make myself care. I imitated the shapes and ideas of trendy designers, but felt like an impostor. I looked to my peers who seemed to love design and wondered, “How is it different for them?”

In a moment of blinding insight, I realized that they had been curious about architecture from when they were little. They had spent their whole lives looking at buildings, building up a mental database of what they liked, what they didn’t like, what they thought they could improve. And now, finally, they could make it real.

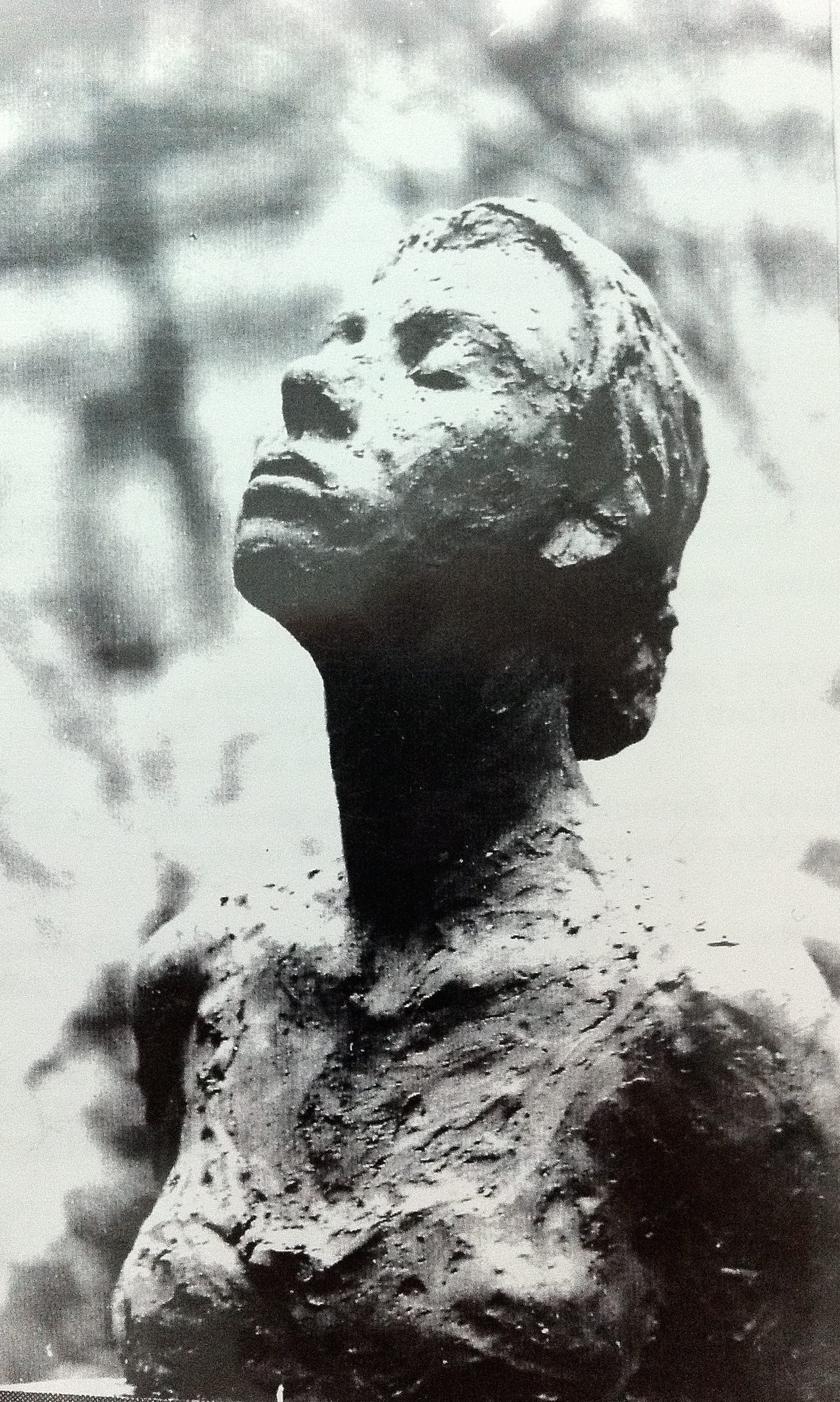

By contrast, I had not spent a single moment of my life thinking about buildings. I had spent time looking at ballet dancers and how their bodies moved. I had gazed at sculptures in museums and sketched human figures in my class notes. I loved the human body in motion. Not accidentally, my first A+ in Architecture School was my sculpture class, where I made a life-sized bust of myself.

Even though it was my first time sculpting something at this scale, I felt sure I could shape the slope of a nose, the curve of a mouth or the plane of a cheek. I knew I still had a lot to learn, but I also felt confident in my work. I had a vision. I had an opinion of what was good. And I was implementing it to the best of my skills at the time.

This was when I formed my first hypothesis about how to choose a career: I realized then that I couldn’t force myself to be interested in architecture, and that I would always fall short compared to those who were. I couldn’t pick a career for its income or social respectability, then mold myself in its shape. If I did, I would feel like an impostor forever.

By contrast, if I followed my curiosity, if I noticed what I had an opinion about from long observation or experience, then I had a chance. My natural interest would lead me to continuous improvement, I would have a rich landscape of ideas to draw upon when I needed to create something, or make a difficult decision. It was scary to start here, because I worried that I wasn’t interested in prestigious- or lucrative-enough careers. But I knew that the alternative was worse, so I decided to take the plunge.

And please, tell your friends!